Dante on Screen: the Helios and Milano Infernos (1911)

"Few if any pictures screened on the fields have created such sensation".

"Remember 3 days only, and at matinees.

Souvenirs given away to the ladies.

Be sure and get a little devil".

The

Inferno on celluloid

It's a truth universally acknowledged, as a great English writer might put it, that Dante's

Divina Commedia

marked the first, and definitive, milestone in Italian literature. Much less well known, however, is the fact that the first film adaptation of the

Inferno, the first

cantica of Dante's epic poem, made in Italy at the very beginning of the silent period by the

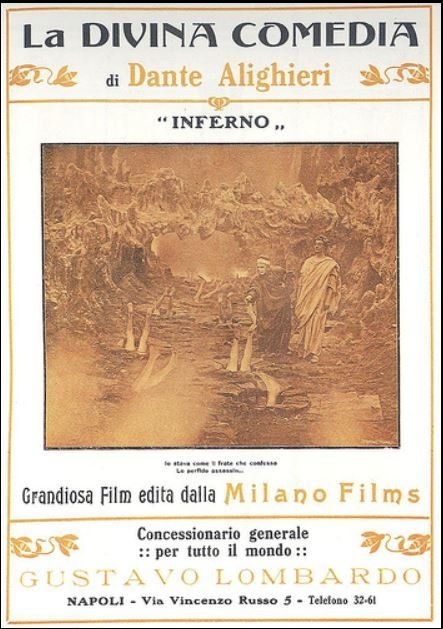

Milano Films company, represented a similar landmark in Italian ̶ and, indeed, world ̶cinema.

Released both at home and internationally in 1911, only six years after filmmaking had really begun in earnest in Italy, and at a time when most films everywhere were still only one or two-reelers usually lasting no more than 20-30 minutes, the Milano Inferno distinguished itself in two ways. First, it shouldered the daunting task of transposing such a great and complex literary work into the newly-established art of the moving image. Second, it did so by adopting the format of what would become the standard model of the full-length feature film, that is, lasting well over an hour (the original program actually said two hours), and so able to provide a whole evening's entertainment. This was thus a truly groundbreaking film, opening up new vistas for the cinema.

Basing films on literary works had easily slipped into being a common practice in filmmaking generally, but it emerged as a particularly strong tendency in the earliest days of the Italian silent cinema. Adaptations ranged widely from attempted transpositions of the sensationalistic best-sellers of popular literature to the venerated major works of the Western canon. Given the intensity of its dramatic stories and the variety of its memorable characters, Dante's Inferno had quickly attracted the attention of filmmakers as source material for their moving pictures. As early as 1907 the American Vitagraph company had released a 16 minute Francesca di Rimini, although arguably based more on theatrical representations of Dante's most seductive sinner than on Dante's own text. Early in 1909 in Italy, the Turin-based Itala company had issued a similarly-short but highly praised Il Conte Ugolino. In the same year the newly-constituted SAFFI-Comerio Company, headed by pioneering documentary filmmaker and official photographer to the Royal House of Savoy, Luca Comerio, decided to take the bull by the horns and embrace the ambitious project of a filmic adaptation of the whole Inferno.

As daunting as the project must have been, it had clearly made quite some headway if in late 1909 the company was able to present sections of what it had already managed to create, if only under the more hesitant title of Saggi dell'Inferno dantesco, at the first International Film Competition in Milan, garnering much critical praise for it, and being awarded a Gold Medal by the Italian Department of Industry and Agriculture. By this time, however, completion of the project had come to be at risk due to the company's financial difficulties. A solution soon emerged, however, as Luca Comerio willingly left the company in order to continue making his prize-winning documentaries, and the SAFFI-Comerio morphed into Milano Films, with a new Board of Administration made up largely of the cream of the crop of Milanese nobility, which included, among others, the venerable names of Count Pier Gaetano Venino (Chairman), Prince Urbano Del Drago, Baron Paolo Airoldi di Robbiate and Count Giovanni Visconti di Modrone. These entrepreneur noblemen brought with them a new and much needed injection of capital but, most importantly, also strong moral support for the Inferno project which they came to regard as a fitting contribution to fulfilling their philanthropic duty to educate the populace and help spread Italian culture. When in May 1910 the company was able to finance the construction of a large new studio complex with the most up-to-date facilities, the co-directors, Adolfo Padovan and Francesco Bertolini, were given the green light and the Inferno project was back on track to completion.

Two Infernos?

Despite the studio's efforts to keep what had become a mega-production under wraps, the contrasting stratagems of the film's designated distributor, Gustavo Lombardo (later to found his own production company, Titanus) in continuing to leak information about the film's coming release, attracted the attention of Helios Film, a small recently-formed film production company, based in the small Southern Italian city of Velletri.

With the intention of exploiting for its own benefit all the public interest and excitement which Lombardo's publicity campaign for the Milano Films' big-budget

Inferno was continuing to generate, the Helios company threw itself into production and in January 1911 was able to release its own

Inferno, beating the release of the Milano Films' version by close to three months. Lasting less than 20 minutes, and with its limited budget and hasty production very much on view, the film exhibited no pretensions to completeness – its 23 scenes and 18 inter-titles patently presenting only a smattering of characters and events from Dante's journey among the damned – but, though inevitably criticised for what it had failed to do, it also managed to attract a modicum of praise for its effort, not least because within six months it had also managed to film and release a follow-up

Purgatorio.

The Milano Films'

Inferno

In contrast to the Helios production's rough-and-ready manner, the Milano's approach was more respectful and, above all, systematic. Not making the film simply for profit but motivated, at least in part, by a pedagogical intent, the company committed a lot of time, effort and resources to what it regarded as a major project. The film was in the end reputed to have cost 100,000 lira, an unprecedented amount for a film until that time (Helios had, in fact, only spent 8,000 lira and, indeed, it showed). Most importantly, it dared to adopt a much longer format which allowed it to follow Dante systematically as he progressed through his myriad infernal encounters. Structured as three parts consisting of 54 scenes and 61 inter-titles, the film was thus able to portray Dante's epic journey close to its entirety rather than just furnishing snippets, as the Helios production had chosen to do (patently acknowledging how little of the journey it had actually covered, Helios also released its film under the title of Visions of Hell). Importantly, the length and the systematic approach allowed the makers to portray Dante's psychological and moral development, progressing from his naivety in the earliest cantos where he partially empathises with the sinners, to being able to kick heads and tear out the hair of one of most heinous sinners stuck in the frozen lake of Cocytus, significantly only a stone's throw away from looming Lucifer himself.

Sensibly, the visual style of the film came to be modelled on the illustrations of Gustave Doré which had circulated widely in Italy, not least featured in an authoritative edition of the Commedia published in the 1860s by the Sonzogno company and edited by Eugenio Camerini. The scenes were thus easily recognizable by most people and must have furnished a comforting sense of familiarity. This must have also helped to make the almost wall-to-wall nudity of the damned souls unobjectionable and uncontroversial - indeed the nudity appears to have been hardly noticed by either critics or audiences at the time. Where the Dantean text was most fantastical the creators resorted to a judicious use of the tried and true Méliès stratagems and, mostly, to good effect. It's true that the special effects don't always work as well as they might but the masking strategies in a scene like that of one of the major sowers of discord, Bertrand De Born, who appears headless but holding aloft his own head like a lantern, would probably still shock the modern viewer. Almost unnoticeable now, however, might be the camera panning to follow the characters' movements, which occurs, admittedly only now and then and especially in some of the earlier scenes, since the technique is now an essential part of film language. But perhaps the film's innovativeness and sophistication of film language emerges most clearly in its use of flashbacks in the pilgrim's encounter with the three most memorable characters of Francesca, Pier della Vigna and Ugolino, a strategy which allows it to present discrete stories within stories, highlighting and reproducing Dante's own great gift for embedding narratives within narratives everywhere in the Commedia.

In creating a first-class artistic product, the company also did well to choose Gustavo Lombardo as exclusive distributor for the film. A great pioneer and innovator in the field of film distribution in Italy, Lombardo continued to leak "indiscretions" about the film as it was being made in his own trade journal, Lux (while, from the same pages, eventually excoriating the Helios version when it was released). When the film had been completed Lombardo organised gala premieres with invited audiences and even engineered a special preview for the King of Italy, a move that stood the film in good stead in its distribution both at home and abroad. The invited audience at one of the most glamorous gala premieres, one held at the prestigious Teatro Mercadante of Naples, numbered many of the most important names of Italian culture at the time, including the philosopher Benedetto Croce and well-known writers, Roberto Bracco and Matilde Serao. In a review in a major newspaper the next day, Serao confessed to herself, and all her fellow intellectuals, having been enthralled by the film the previous evening and now being converts to the notion of cinema as an art form. This was publicity you couldn't pay for. In addition, the canny Lombardo immediately set about, and succeeded in, getting the film officially registered as copyright, another important first in the history of Italian cinema.

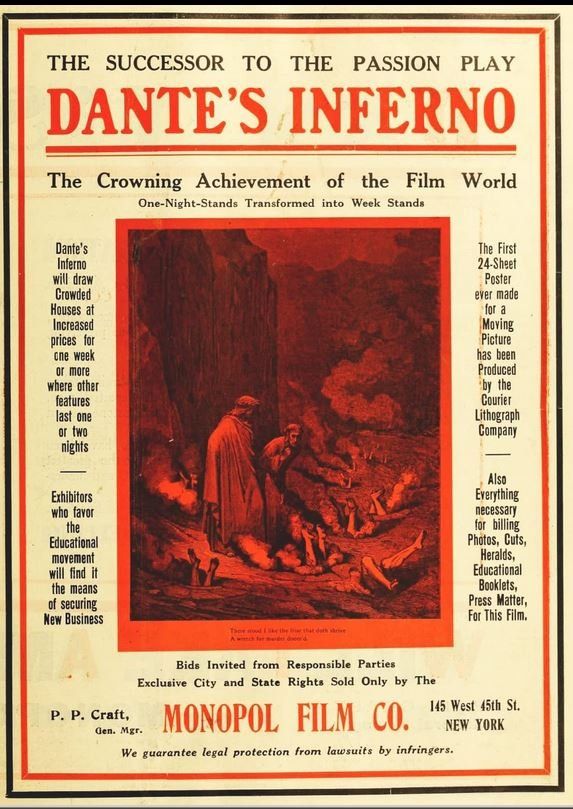

For its international distribution, Lombardo licensed the Paris-based Monopol Film Company which then distributed the film through its subsidiaries in Britain and America. Lombardo also organised a special screening in Paris after which Ricciardo Canudo, the famous early theoretician of cinema as art, greatly praised the film in the public lecture he held on Dante at the École des Hautes Études. Its subsequent release in Britain characterised it as "The Film Masterpiece of the Immortal Literary Masterpiece" and the film became a huge box office success. The film similarly impressed in America where the much-respected trade journal, The Moving Picture World, judged it to be "exceedingly faithful to the words of the poet". It suggested that what had been created was a "Dante intelligible to the masses" and that: "To the artists, who have given us this visualization, we owe a debt of gratitude second only to that due to the great poet himself". The reviewer in The New York Dramatic Mirror concurred with such high praise, styling the film "a vast and wonderful achievement [...] that shows to what heights the motion picture can attain in treating a great subject".

Two Infernos in Australia

Especially for Australian lovers of Italian cinema, it's interesting to note that both films also made it Down Under. Perhaps it's unsurprising that the Helios film arrived in Australia first, although it is surprising that the Milano version, given the success it had immediately achieved internationally, took so long to get here.

The Helios Inferno is recorded as arriving in Australia in May 1911, opening in Sydney at J.D. Williams' Lyric Theatre on 22 May in a program featuring, as was the widespread practice at the time, four other disparate films. It was advertised as "A Masterpiece in biographical art" whose exclusive rights in Australia been purchased "at enormous expense" by Mr J. D Williams. In his typical showman style, Williams promised that 500 little devil souvenirs would be given away at the event. There were continuous screenings on the hour and The Bulletin reported that, nevertheless, there continued to be crowds outside waiting to get in. Two weeks' later the film moved to Tasmania where on 7 June it appeared in Launceston, in a program also featuring a version of The Marriage of Figaro made by the Italian Cines company, and with the accompaniment of what was described as a "Tannhauser score". It subsequently screened in Hobart (12 June) before beginning to travel the breadth of the Wide Brown Land, starting with Kalgoorlie, where it attracted crowded houses at the Theatre Royal for a week, always in programs that included several other films. A newspaper report around the end of its run highlighted the film's "most striking realism" and suggested that: "Few if any pictures screened on the fields have created such sensation". It then moved to Perth where, beginning 4 July, it appeared for a week at the Shaftsbury Gardens Cinema; press reports specified that it was a 23-scene coloured photoplay, confirming for us that, contrary to popular belief, silent films were often coloured. At around the same time it surfaced in several locations in regional Queensland, appearing on a double bill with a Vitagraph A Tale of Two Cities on 3 July at Fowler's Pictures in Maryborough and a day later at West's Pictures in Gympie. In August it settled into a solid season in Melbourne at the Lyric Theatre, in Prahran (only shown in the evenings because "quite beyond the comprehension of children" but "a most artistic and impressive presentation"). At the end of August it had another short season in Tasmania. In September it was shown at Bendigo's Lyric Theatre (11 September ) and at the end of the month (26-27 September) at Brisbane's Earl's Court Cinema. It then had another season at Port Adelaide's Empire Picture Palace (23-28 October) although by this time it had acquired something of a rival. At the beginning of October the Prahran Lyric Theatre had begun showing what it advertised as "The most comical pantomime ever !! / Pathé Frères' travesty, / HELL UP TO DATE! / A Screaming Burlesque of / Dante's Inferno. / A Gorgeous Absurdity! / The Ridiculous Adventures of Satan / and his Naughty Son / in their Own Little Warm Home!!!". It's difficult to tell how much such a spoof may have impacted on the Helios film's own drawing power. Whatever the case, it does seem that, following its Adelaide season that year, the film disappeared from sight.

The international reputation of the Milano Films'

Inferno appears to have only begun to filter through to Australia in the first months of 1912. Following scattered reports about the film's extraordinary success overseas, in June the Sydney papers began to carry the announcement that negotiations to bring the film to Australia with rights holders, Universal Films, had concluded successfully, and the film would premiere at the Sydney Town Hall on 3 July. It's worth noting that, at the time, the Helios version was still showing, if only sporadically, in small regional towns like Ballarat (at the Coliseum on 2 May) and Geelong (the Mechanics Hall, 25 June).

Throughout June, repeated announcements regarding the upcoming premiere of the film built up expectations. On 3 July, all the Sydney newspaper advertisements for the event began with the statement "This film must not be confused with any other by the same name", which had been one of the conditions which Lombardo had imposed on distributors, mandating that such a declaration be prominently displayed whenever and wherever the film was being shown. After a long quote from the laudatory review of the film in The Moving Picture World, the advertisements also printed the translation of a letter of commendation of the film from the King of Savoy, before providing the details regarding screening times and prices. Bizarrely, printed in the next column – literally alongside it in the Sydney Morning Herald – the American Picture Palace advertised its day's program as: "A Mammoth Star Program including DANTE'S INFERNO: A Masterpiece Sensational Dramatic Photo-play / holding the audience spellbound". At the same time, slightly above it, the advertisement regarding what was on offer at J.D. Williams' Lyric Theatre, announced the screening of what it called "The World's Great Masterpiece, The Sensation of All Sensations, Helio's [sic] Divine Comedy: today DANTE'S INFERNO". It clarified that it would be shown only at matinees and ended with the injunction to "Remember 3 days only, and at matinees / souvenirs given away to the ladies./ Be sure and get a little devil". Thus, in the most uncanny way, it would seem that the old rivalry between the versions was coming to being played out in the Great South Land thousands of miles away from where they had both originated! In what could have been a response to Williams' little devils offered at the door, but indeed may have been intended all along, the premiere screenings of the Milano version at the Town Hall included the presence of what was reported in the press as "a scarlet-clad interpreter, presumably intended to represent Mephistopheles, who delivers a preliminary lecture".

At the end of its premiere at the Sydney Town Hall and, as always, introduced in the papers by the declaration that it must not be confused with its impostor namesake, the Milano Inferno moved to a three-day season at Brisbane's His Majesty's Theatre (9-11 July). After single screenings in regional towns in NSW – at Tamworth (19 July) and Maitland (22 July) – it moved to four days at the Melbourne Town Hall (9-12 August). On its way back to Sydney it had one-night stands in Wellington (16 August) and Dubbo (17 August) before another three-day season in Sydney at the Burlington Great Star Picture Theatre (19-21 August). It was subsequently shown for 6 nights in Adelaide at the Town Hall Wondergraph (21-26 August) and then a single screening in Bathurst (4 September) before another very solid season in Melbourne where it screened at both the Brunswick and the Fitzroy Lyric Theatres and at the Hoyts in the St George Mall at the same time (23-29 September). After surfacing for a night in Townsville (9 October) it appears to sink out of sight for several months before reappearing on 14 March 1913 at the Snowden Cinema in Melbourne. It was back in Adelaide for six nights, beginning 7 May. At the end of May it had a single screening in the regional NSW town of Hay. Ironically, advance publicity underscored the fact that this was not the same as "the awful imitation picture" shown previously, presumably referring to the Helios version; in the event, from a subsequent press report, the Hay audience seemed to have also found this version disappointing). After single screenings in a number of other towns in regional NSW - at Junee (28 August), at Cootamundra (30 August), and again in Maitland (3 September), its last reported screening in Australia would seem to have been in the Protestant Hall, Queanbeyan, on 27 September, thanks to the generous intervention of the curiously-named Swastika Picture Company.

A Milestone Lost and Found

The historic leap forward achieved by the Milano Films' Inferno rather faded from view in the following years as Italian cinema went through its first Golden Age. By the time Italy joined the First World War, the apex of that production would be regarded as having been reached not by an adaptation of Dante but by the Itala company's Cabiria, a stunningly extravagant and monumental three-hour epic set in Roman times. While there would be many films about Dante, or drawn from parts of his Commedia, in the following years, there would be no other attempt to film the entire Inferno. A lack of interest in those years regarding the cinema of the silent period further contributed to erase the memory of the Milano's cinematic milestone. However in the 1980s, a scholarly revival of interest in the history of Italian silent cinema led to a reappraisal of the film's place in that history, a reappraisal aided by a rediscovery of more complete copies of the film. In 2007 a careful restoration of the film was carried out by the Bologna Cínemathèque, and later released on DVD. It is now also freely available on YouTube (as below).

Gino Moliterno is a Senior Lecturer in Film and New Media at the Australian National University.